Unsolved Murder of Kimberly Pitchford

In the early 1970s, a sinister shadow loomed over Houston. While Corll, Henley, and Brooks murdered 27 teenage boys, another killer targeted a dozen young women.

It's been five decades since 16-year-old Kimberly Pitchford vanished from the parking lot of J. Frank Dobie High School in Houston, Texas, on January 3, 1973. The shy sophomore had just finished her first driver's ed class that concluded at 6 p.m. and was supposed to call her parents for a ride home, but the call never came. Two days later, her partially clad body was found 30 miles away, floating in a canal beneath a wooden bridge in Brazoria County on County Road 65, in Iowa Colony, Texas. She'd been strangled, and her case remains unsolved.

It was also the first day of school after the Christmas holidays when Pitchford was abducted and her lifeless body was found in a rural area of Brazoria County, where bodies of other young women had been found in 1971. This raised the question - was her murder the work of a fifth killer to emerge from the shadows, or was she a victim caught in a twisted game orchestrated by a sole predator to taunt police?

Investigators from the Brazoria and Harris County sheriff's offices teamed up and divided the interviews of Pitchford's family members, classmates, teachers and other possible witnesses to help piece together what may have happened during the final days of the teen's life that would cause her to cross paths with a killer.

According to her father, Elmer Pitchford, now deceased, the family filed a missing person report when she failed to call or arrive home that evening. Kim was prompt in letting them know her whereabouts and knew to get permission before changing her plans.

After speaking with the teen's best friend, Karen Fram, the family learned that Kim had borrowed money from her for lunch that day and was upset over her boyfriend, Jimmie Maddox, being in jail.

Maddox, now 67, was just 17 when he joined the U.S. Army in 1972 and was home on leave since the Christmas holiday. According to Maddox, he and two of his buddies had met Kimberly and her friends at the Trampoline, a popular teen hangout located on Kleckley Drive across from Almeda Mall, on Dec. 31, 1972, to celebrate New Year's.

Before midnight, Maddox's friend, Ray, drove everyone to Kimberly's house in the 8500 block of Wynlea where they all hung out and visited. Maddox and his friends, Ray and Phil, began wandering down the street and were arrested by police for breaking into cars. Ray and Phil were released on January 2, but Maddox was detained for being AWOL.

"I never saw Kimberly since that night," said Maddox. "I didn't even get to go to her funeral. She was a sweetheart, and I've often wondered what might have happened between us because I was definitely going to contact her after I was discharged from the Army."

According to Maddox, Kimberly was a straight-laced young woman who spoke highly of her family and had no reason to run away. "I was the wild one and wasn't even allowed to smoke if I wanted to be around her," Maddox said.

The puppy love was mutual, and according to teachers, Kim was visibly upset during her sixth-period class as well as the D-Hall she attended prior to driver's ed. Maddox was unaware that Kim was worried about him.

Two of the last class-mates to see Kim alive were Russell Sones and Jimmy Hester. According to Sones, he was Kim's driving partner. "Mr. Arthur Clark was our instructor, and I didn't really know Kim that well, mostly just in passing. I was real shy back then and didn't notice if Kim seemed upset or not because I was focused on driving. She sat in the back seat while I drove and then we'd switch. We drove through the nearby neighborhood and parked along the side of the high school facing the baseball field. When we got out of the car, I didn't notice which way she went," said Sones.

Hester had been waiting the entire hour in the school's doorway facing the parking lot for his class to start at 6 p.m. "I remember seeing Russell get out of the car, but I didn't see Kim. I knew who she was, but I didn't know her personally," said Hester. "I don't recall seeing anything out of the ordinary."

It was as if Kimberly vanished into thin air before her body was found off a rural road in Brazoria County.

Law enforcement worked tirelessly on her case for several months and conducted dozens of interviews and ran down every lead that came their way, to no avail. Today, Brazoria County investigators continue to review the case on occasion hoping to notice a detail that might have been overlooked or receive a tip that helps solve the case.

Edward Harold Bell

In 2011, a serial flasher and former psychiatric patient named Edward Harold Bell, now deceased, claimed he was responsible for the murder of Pitchford, as well as the murders of at least 11 other young women in the early 1970s.

Bell made this claim while serving a 70-year sentence for the August 28, 1978, murder of Larry Dickens, 26, who literally caught Bell with his pants down flashing neighborhood girls in Pasadena and took away his car keys to prevent his escape. When Dickens refused to give Bell his keys, Bell put on his pants and reached for his .22 automatic pistol under the seat and fired a warning shot into the air and threatened Dickens to return his keys. Dickens refused again and was shot repeatedly and staggered to his driveway with Bell still in pursuit of his keys. After Dickens relinquished the keys, Bell went back to his truck, grabbed his rifle, and turned to fire a final fatal shot into Dickens' head.

For Bell's claim to be within the realm o f possibilities, one must ponder the likelihood of a seasoned sexual serial killer regressing seven years later to acts of exposure in front of children.

The question was posed to former FBI profiler Mark Young, who is now in private practice with YoungTex International. "It generally follows that a sexually motivated serial killer continues with that type of behavior. There may be gaps between offenses due to many factors such as incarceration, old age, police activity, availability of victims while the offender is on the prowl, employment elsewhere, family intervention, or many other variables," said Young. "We have rarely, if ever, seen a prolific offender, completely change and become a noticeably lesser offender or, as you questioned, to go from the serial killing of many young female victims to only exposure and masturbation in front of children."

Bell never provided any details on the unsolved cases that weren't already published in old newspaper reports.

Could other cases be connected?

Although Pitchford's case appears to be an isolated incident, she was in fact the 12th young woman to be murdered in the surrounding area of Houston since June of 1971 and the third victim abducted from the South Belt area. The series of murders spans four counties and are collectively known as the "Mysteries of I-45."

Colette Wilson, 13, vanished on June 17, 1971, from the intersection of County Road 99 and Highway 6 in Brazoria County. Her skeletal remains were found November 26, 1971, 40 miles away, near Highway 6 and Clay Road, at the Addicks Reservoir adjacent to the Spring Branch subdivision. A second set of remains belonging to Gloria Gonzales, 19, was also found. Gonzales, a bookkeeper, lived in the 2000 block of Jacquelyn Street in northwest Houston and had been missing since October 28, 1971. Wilson died from a blow to the head, and Gonzales had been strangled.

Brenda Jones, 14, resident of Galveston, disappeared on July 1, 1971, after she walked to the hospital to visit a relative. Her nude and bound body was found floating in Galveston Bay near Pelican Island the following day. Jones had been strangled.

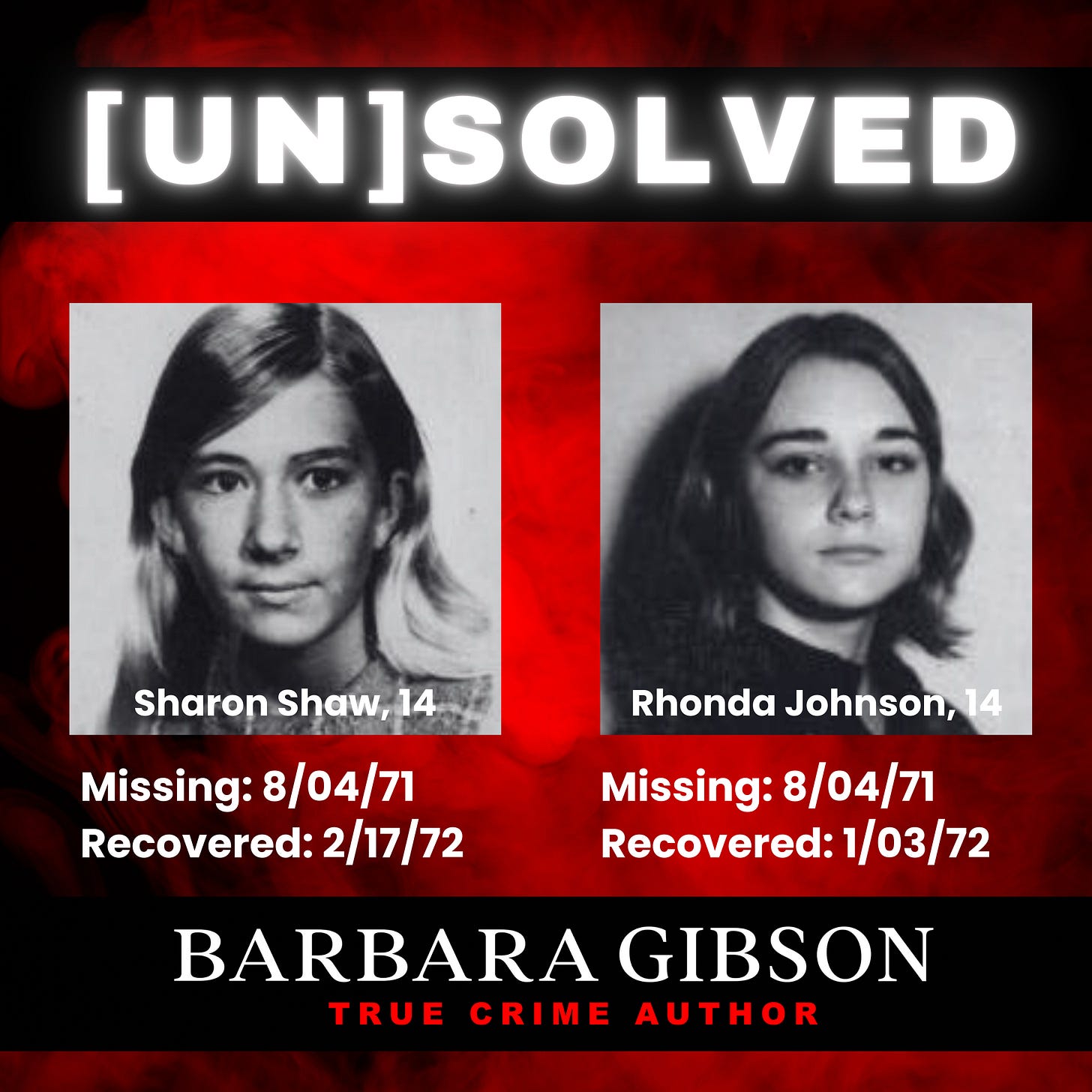

Rhonda Johnson of Webster and Sharon Shaw of Nassau Bay, both 14, were last seen on August 4, 1971. It was reported that the pair hitchhiked to Galveston to visit a surf shop; however, their bodies were found in a ditch near the intersection of Bay Area Boulevard and Red Bluff, 10 minutes from Shaw's home in the 1500 Block of NASA Road 1. The headless body of an unidentified teen male was also found in the same area on September 1, 1971.

Adele Crabtree, 16, a runaway from Ohio living in Houston, was last seen trying to hitchhike a ride to work on November 2, 1971. Her body was found the following day in Conroe and had been shot twice by a shotgun.

Linda Faye Sutherlin, 21, a key punch operator for IBM, was last seen at 12:30 a.m., November 4, 1971, on Telephone Road. Her body was found in a ditch near the intersection of FM 518 and CR 89 in Pearland on November 7. She'd been beaten, strangled and shot multiple times by a shotgun.

Alison Craven, 13, was last seen at her apartment located on Kingspoint near Almeda Mall on November 9, 1971. Her partial remains were found on January 29, 1972, in a field near her apartment with the remaining half being found on February 25, 1972, in a field 4 miles away from Sutherlin's body in Pearland. The Craven family also owned a home on Eddyrock located a couple of blocks from Dobie High School.

Debbie Ackerman and Maria Johnson, both 15 and students at Ball High School in Galveston, vanished after going to an area mall on November 15, 1971. Their partially nude bodies were found in Turners Bayou in Texas City on November 17-18. Both victims had been bound and shot.

Mildred JoAnn Knighten, 15, was last seen the evening of October 20, 1972, leaving her parents' home on Old Galveston Road in southeast Houston. Her partially clad body was found on October 23 dumped near a construction site in Pasadena; she had sustained more than 50 stab wounds. Until April of 1972, Knighten lived within 2 miles of Kimberly Pitchford's home.

Despite Pitchfords close proximity to the abduction and/or dumpsites of Linda Faye Sutherlin, Alison Craven and Colette Wilson, no links were publicly made since Sutherlin and Wilson's killer was dead and Craven's killer had already confessed and was in custody prior to Pitchford's death.

Did police catch the correct killer(s)?

News reports of the series of murders went nationwide and prompted Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby to contribute $8,000 toward a reward fund. Multiple law enforcement agencies joined forces and between April and June of 1972 police had arrested and obtained confessions from four different men that solved a majority of the cases.

Harry Andrew Lanham, Jr., 25, a Houston wrecker driver, confessed on April 15, 1972, that he was present when Linda Sutherlin was murdered but pointed to Anthony Michael Knoppa, as being the triggerman. Lanham made a second statement on June 9, 1972, implicating himself and was also charged with the murders of Colette Wilson and Gloria Gonzales.

Henry Doyle Shuflin, Jr., 22, a Vietnam veteran and son of a U.S. Air Force master sargent, confessed on May 2, 1972, to the murder of Alison Craven.

Anthony Michael Knoppa, Jr., 24, a Vietnam veteran, confessed on June 6, 1972, to being present when Linda Sutherlin was murdered but claimed Lanham was the trigger man.

Michael Lloyd Self, 25, a gas station attendant and a volunteer firefighter, confessed on June 9, 1972, to the murders of Rhonda Johnson and Sharon Shaw.

All four men claimed the statements were false and were the result of coercion by law enforcement. Shuflin was under psychiatric care and stated he was easily pressured. Self claimed that Donald Ray Morris, the Webster police chief, held a gun to his head and demanded that he confess. Morris was arrested years later moonlighting as a bank robber.

Lenham and Knoppa were tried separately, but at the same time in Brazoria County in October of 1972, which gained national media attention. Both men took the stand in their own defense with Lanham stating that Brazoria County officials had made a deal with him to protect his wife in exchange for his turning state evidence on Knoppa. It was also his understanding that the second statement he signed on June 9, which implicated himself, was just a formality that couldn't be used against him. Lanham stated that the authorities had shafted him with lies.

When Knoppa took the stand he testified that the entire statement he signed on June 6 was false, and he had written it while being coached by law enforcement after he'd been beaten. He further claimed that he'd been told that he might be shot "while trying to escape." An ominous statement that would come true, but not for Knoppa.

The jury didn't buy their stories, and on October 20, 1972, the jury came back with a guilty verdict for both defendants, with Lanham receiving 25 years and Knoppa receiving 50. Law enforcement had succeeded in getting two of the worst killers off the streets, but by that same evening, 15-year-old Knighten vanished after she left her family's home in southeast Houston. Her mutilated body was found three days later.

After the trial, Lanham was transferred to the Harris County jail to await trial for the murders of Colette Wilson and Gloria Gonzales. Montgomery County officials were also in line having dropped charges against their suspect for Adele Crabtree's murder as a result of Lanham's confession. But on December 30, 1972, Lanham was shot and killed by authorities while trying to escape with two other convicts.

Four days later on January 3, 1973, Kimberly Pitchford disappeared.

my name is kaye pitchford I cant help wondering if Kim had been related could you please tell me if her father was david or earl my cousins thank you kaye pitchford